By: William Arnone and Jay Patel

Published: May, 2020

Each year, the Report of the Social Security Trustees updates projections about the future finances of Social Security’s two trust funds, the Old-Age and Survivors (OASI) Trust Fund and the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund. The 2020 Social Security Trustees Report projects that revenues will be sufficient to pay all scheduled benefits until 2035 and three-quarters of scheduled benefits thereafter. The DI Trust Fund is now projected to cover scheduled benefits until 2065 (compared with 2052 in last year’s Trustees Report), and the OASI Trust Fund until 2034 (the same projection as last year’s report). On a combined OASDI basis, Social Security is fully funded until 2035 but faces a projected shortfall thereafter if Congress does not act before then.

The 2020 Trustees Report shows that Social Security income from payroll contributions, tax revenues, and interest on reserves exceeded outgo by $2 billion in 2019. Reserves, now roughly at $2.9 trillion, are projected to begin to be drawn down in 2021 to pay full scheduled benefits. After the projected depletion of the combined OASDI trust funds in 2035, Social Security contributions and tax revenues would continue to be received and would cover about 79 percent of scheduled benefits (and administrative costs, which are less than 1 percent of outgo). Timely revenue increases and/or benefit reductions could bring the program into long-term balance, preventing the projected shortfall.

Crucially, the 2020 Report does not take into consideration the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on projected OASDI revenues and outlays. For this reason, next year’s report will be of great significance to the policymaking community.

What is the Trustees Report?

The Social Security Act established Boards of Trustees for the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, respectively, and requires the Boards to report annually to Congress on the status of the funds.1

The 2020 Social Security Trustees Report updates projections of the finances of Social Security’s two trust funds, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund. The Trustees Report is a tool to help Congress and the public gauge the financial status of the Social Security system. Social Security’s financial balance is projected over 75 years, longer than almost all other government or private-sector projections. This requirement reflects the long-term commitments of Social Security and the critical importance of this program to American workers. Any projection over so long a period is inherently uncertain. Nonetheless, the Trustees’ projections provide policymakers the information they need to plan for the future. The 2020 report is the 80th to be issued and is available on the website of the Office of the Chief Actuary of Social Security: www.ssa.gov/OACT.

Who pays for Social Security?

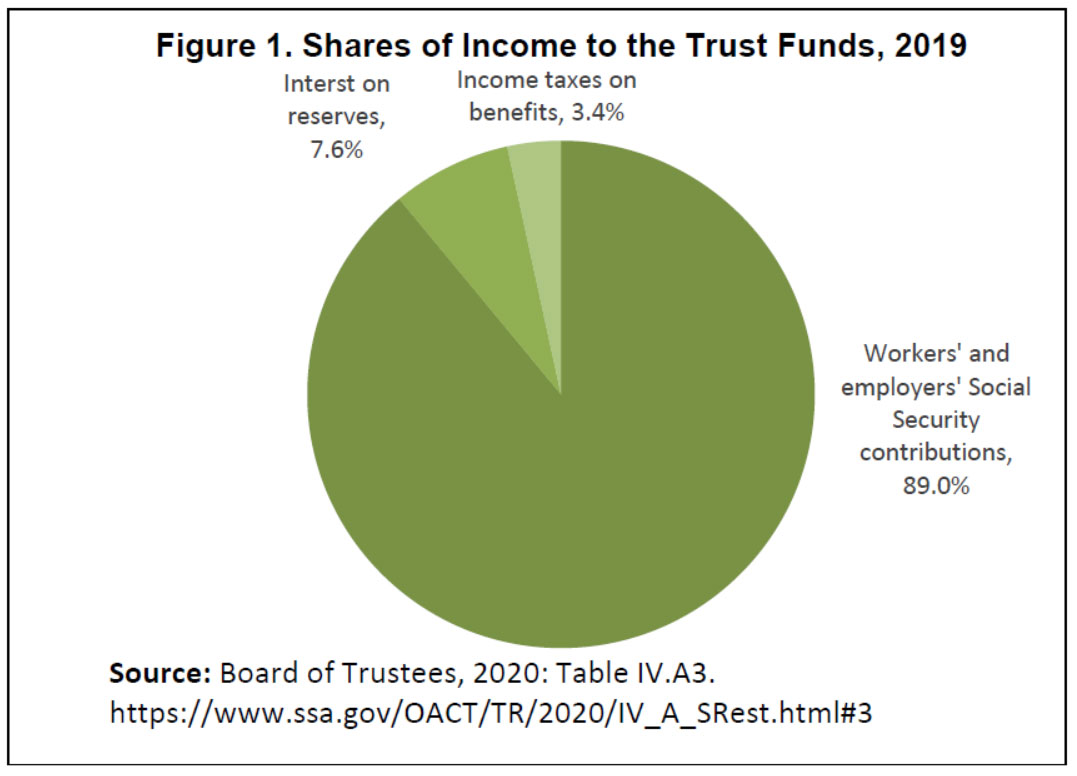

Workers and employers pay for Social Security through mandatory contributions under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). Workers and employers each pay 6.2 percent of earnings up to an annual cap, which is $137,700 in 2020. With the sunsetting of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015’s provision on the reallocation of funds from OASI to DI, rates have returned to post-2000 levels: 0.9 percent of Social Security payroll contributions are paid to the DI Trust Fund, while the remaining 5.3 percent goes to the OASI Trust Fund. Self-employed workers pay both the employee and the employer share and may deduct the employer share from their taxable income. Higher-income beneficiaries pay income taxes on part of their benefits. Part of this income-tax revenue goes to the Social Security trust funds, and part goes to the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund.2 Interest on Social Security’s reserves provides an additional source of program income. The reserves are invested in special- obligation U.S. Treasury bonds, which earned an effective interest rate of 2.8 percent in 2019.3 Worker and employer contributions accounted for about 89.0 percent of trust fund income in 2019, while interest on reserves accounted for about 7.6 percent, and income taxes paid by beneficiaries accounted for 3.4 percent (Figure 1).

Who receives Social Security?

Social Security pays monthly benefits that replace part of the earnings that are lost when a worker who has paid into the program for specified periods becomes disabled, retires, or dies. In January 2020, 64 million Americans, or almost one in five, received Social Security benefits.5 Over one family in four received income from Social Security.6 In 2019, the system paid out $738 billion to 45.1 million retired workers, $104 billion to 4.0 million widows and widowers, and $33 billion to more than 2.4 million spouses.7 More than $35 billion was paid out to 4.1 million children either under the age of 18 (19 if still in high school) or disabled since childhood. About 8.4 million disabled workers received benefits, totaling almost $137 billion in 2019.8.

How much does Social Security pay?

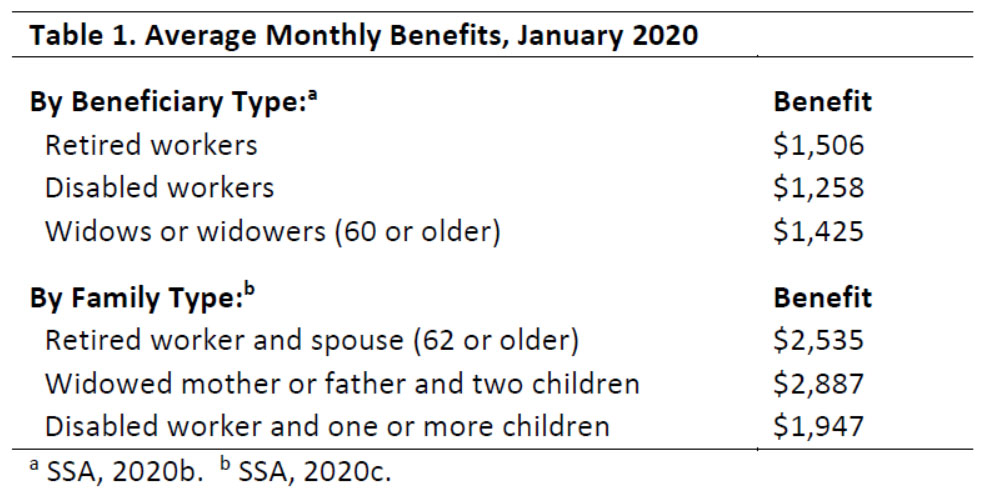

The average monthly benefit paid to all retired workers in January 2020 was $1,506, or about $18,072 annually (Table 1).9 The average monthly benefit was somewhat smaller for disabled workers ($1,258) and for widows and widowers age 60 or older ($1,425)10. Benefits are higher for families. For example, widowed mothers or fathers with two children received $2,887 a month, on average, or about $34,664 a year, while disabled workers with one or more children received $1,947 a month, on average, or about $23,364 a year.11 For comparison, the 2019 federal poverty guideline for an individual is $12,760 a year; for a family of two it is $17,240; and for a family of three it is $21,720.

Social Security is the main source of income for most beneficiaries age 65 and older.13 For almost half of married beneficiary couples and over two-thirds of unmarried beneficiaries age 65 and over, Social Security accounts for more than half of total income.

Social Security benefits are adjusted each year by an automatic cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) that is based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). Because the CPI-W increased 1.6 percent from the third quarter of 2018 to the third quarter of 2019, Social Security benefits increased by 1.6 percent in December 2019.

Retirement benefits may be claimed as early as age 62. Benefits increase by approximately 6-8 percent for each year a worker defers claiming up to age 70. At age 70, the monthly benefit is 176 percent of that payable at age 62. 27.4 percent of male retirees and 31.0 percent of female retirees who claimed benefits in 2018 claimed at age These figures have been declining since the early 2000s after peaking at 50.3 percent for men and 55.0 percent for women in 2004.16 Those who claimed at 62 received 25 percent less than they would have received had they claimed at age 66 and 43 percent less than if they claimed at age 70, but their benefits are payable over a longer expected payment period.

A common way to assess benefit levels is to compare workers’ benefit amounts at retirement with their earnings over their working careers. Under current law, the replacement rate for a medium earner (with career-average earnings of $53,757 in 2019) retiring at age 65 is projected to generally decline from 40 percent of career-average earnings in 2020 to about 36 percent in 2025 and thereafter.17 The replacement rate for a medium earner retiring at the early age of 62 is projected to decline from 31 percent in 2020 to 30 percent in 2022 and thereafter.18 The drop in replacement rates is a result of the 1983 Social Security amendments that gradually increased the age at which unreduced benefits are paid from age 65 to 67 for workers born in 1960 and later, with the full shift first taking effect for workers who will reach 62 in 2022 and later. When considering options to close the projected Social Security funding gap, it is useful to take into account reductions in benefits already scheduled under current law.

How do actuaries project the future?

Each year the Social Security actuaries review the performance of the economy, take into account new laws and regulations, modify and improve projection methods, and reassess assumptions about future economic and demographic trends that will affect the Social Security system — such as employment, wage levels, productivity, inflation, interest rates, birth rates, death rates, and immigration.

The actuaries make projections using three scenarios agreed upon by the Trustees: intermediate, low-cost, and high-cost. The intermediate scenario receives the most attention. In general, the low-cost estimate uses assumptions that generate higher revenues or lower overall costs (such as higher economic growth, lower unemployment, higher fertility rates, more net immigration, and lower life expectancy), while the high-cost estimate uses assumptions that generate lower revenues or higher spending. For each scenario, the Trustees Report separately projects the status of the funds for the short term (10 years) and long term (up to 75 years).

What do the Trustees project for the short term?

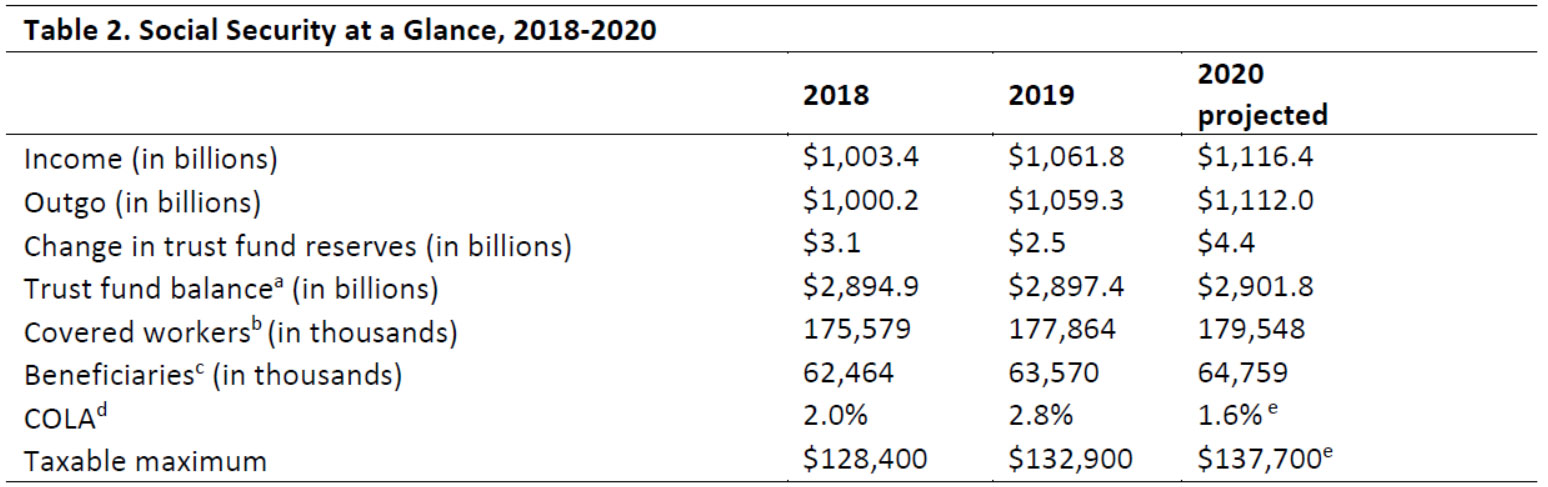

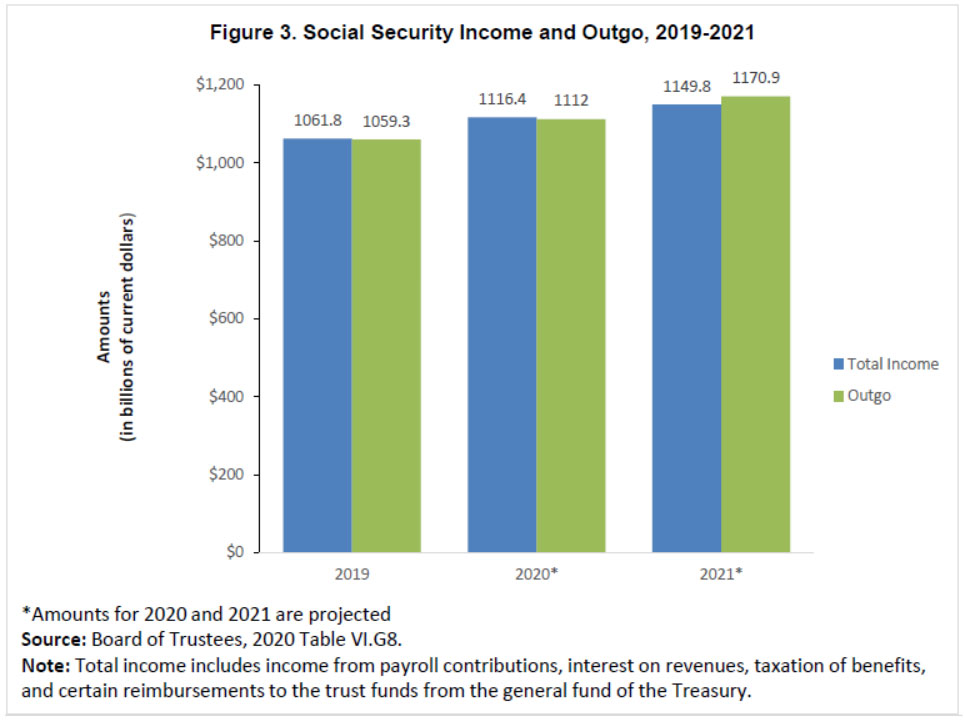

In 2020, the Social Security trust funds are projected to collect $1,116.4 billion and pay out $1,112.0 billion, increasing asset reserves by $4.4 billion (Table 2). Almost all outgo will be used to pay benefits; less than 1 percent of outgo will be spent on administration. Income consists of revenues – contributions from workers and employers and income from taxation of benefits – plus interest earned on the trust fund reserves.

By law, income in excess of what is needed for current outgo is invested in interest-bearing securities guaranteed as to principal and interest by the U.S. Treasury. These assets, accumulated since 1937, make up the trust fund reserves. Since 1937, Social Security has collected $23.9 trillion in revenues and interest and has paid out $21.0 trillion in benefits and administrative costs (as of December 31, 2019), leaving a reserve balance of $2.9 trillion in its trust funds. Under the intermediate assumptions, Social Security outgo will begin to exceed income in 2021 and reserves will begin to be drawn down to pay benefits.

Source: Board of Trustees, 2020: Tables IV.A3, IV.B3. & V.C1

- Trust fund balances shown are as of the end of the year indicated.

- Workers who are paid at some time during the year for employment on which OASDI taxes are due.

- Beneficiaries receiving benefits on June 30 of that year.

- COLAs shown are effective beginning with benefits received in January of the year indicated. Benefit checks are actually received the month after the benefits are payable. SSA records a COLA for the month payable, thus for December of the prior year.

- Actual.

What do the Trustees project for the longer term?

The Trustees Report provides summary measures of projected program income and outgo over the next 25, 50, and 75 years. The Trustees recognize that the reliability of the financial projections declines as the projection period increases. Under intermediate assumptions:

- Over the next 15 years, Social Security income and trust fund reserves can cover all scheduled payments.

- Over the next 25 years, Social Security finances are projected to cover 91 percent of expected outgo.

- Over the next 50 years, Social Security finances are projected to cover 85 percent of expected outgo.

- Over the next 75 years, Social Security finances are projected to cover 82 percent of expected outgo.

These measures of financial self-sufficiency illustrate the extent to which the program’s assets and income are projected to meet future obligations.19 The 25-, 50-, and 75-year projections indicate that remedial actions will be needed to ensure that all legislated benefits will be paid. The Trustees Report highlights other key dates about Social Security’s future finances:

- In 2021, revenue from payroll contributions, interest on reserves, and taxation of benefits is expected to be less than total outgo for the year. If action is not taken in the near future, reserves will start to be drawn down to pay benefits next year.

- Trust fund reserves are expected to be depleted in 2035, if Congress takes no action between now and then to lower outlays or increase revenues. Even if Congress does nothing, after reserves are depleted, revenue will continue to be received in the form of contributions from workers and employers, as well as from the taxation of benefits. This revenue is projected to cover about 79 percent of scheduled benefits and administrative costs in 2035 and 73 percent of benefits in 2094.20 By law, Social Security cannot pay benefits in excess of its income and reserves.

What has changed since last year’s projections?

Social Security’s projected long-term revenue shortfall increased from 2.78 percent of taxable payroll in 2019 to 3.21 percent in the 2020 Trustees Report. The year in which the combined OASDI trust funds would be fully drawn down in the absence of Congressional action has remained the same at 2035. The Disability Insurance Trust Fund’s projected depletion year has, however, been extended from 2052 to 2065.

Year-to-year changes in the estimates are to be expected. Reasons for the changes between the 2019 and 2020 projections are described in Table II.D2 and Section IV.B6 of the Trustees Report.

Some of the variation in the 2020 report can be attributed to the changes in methods and programmatic data but largely stems from legislative, demographic, economic, and disability changes such as: the repealing of the excise tax on employer-sponsored group health insurance premiums (worsens the shortfall by 0.13 percent of taxable payroll); decline in total fertility rate (worsens the shortfall by 0.11 percent of taxable payroll); decrease in estimated birth rate (worsens the shortfall by 0.04 percent of taxable payroll); decrease in real interest rates (worsens shortfall by 0.07 percent of taxable payroll); lowered GDP projection for fourth quarter of 2019 (worsens shortfall by 0.04 percent of taxable payroll); and changing the 75-year projection period by one year (worsens the shortfall by 0.05 percent of taxable payroll). The Trustees’ projection for the year of depletion of the DI Trust Fund has been extended by 13 years since last year’s report. Causes for the DI Trust Fund’s improved outlook include the continuing decline in the number of applications and awards for disability benefits, a more gradual path from current disability incidence rates to the ultimate disability incidence rate, and a reduction in the assumed ultimate disability incidence rate from 5.2 to 5.0 per thousand exposed.

The long-range actuarial shortfall is projected to be 3.21 percent (an increase from 2.78 from the 2019 report) of taxable payroll – that is, 3.21 percent of all earnings that are subject to Social Security contributions. To put this in perspective, the projected shortfall would be eliminated if the contribution rate paid by employees and employers each were 7.9 percent instead of 6.2 percent over the next 75 years.

What do the high-cost and low-cost projections show?

In the Trustees’ high-cost scenario, Social Security’s reserves would be depleted in 2031 (instead of 2035 in the intermediate scenario), and during the first 25 years, the program’s finances would be sufficient to cover 81 percent (instead of 91 percent) of its outgo. In the low-cost scenario, the OASDI trust funds are projected to be depleted in 2079 (in contrast to the 2019 report which projected the low-cost scenario to achieve solvency through the entire 75-year window), but revenue is expected to once again cover full payment of benefits by the end of 2088. During the first 25 years, OASDI’s finances would cover 103 percent (instead of 91 percent) of program outgo*.

The difference among these estimates reflects the great uncertainty about what the distant future holds.

What will happen if Congress does nothing to restore Social Security’s long-term solvency?

The longer lawmakers wait to address Social Security’s long-term shortfall, the more severe the revenue increases and/or benefit cuts required to restore solvency will become. To give a sense of the magnitude of the measures needed and how these become more severe the longer Congress fails to address the issue, one might consider what their magnitude would be if undertaken this year, compared to at the time of projected depletion of the trust funds in 2035.

If Congress were to take action this year to restore 75-year solvency, it would need to:

- Raise revenues by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent contribution rate increase from today’s 6.2 percent rate on workers and their employers to 7.77** percent; or

- Cut scheduled benefits by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent reduction of about 19 percent, applied immediately to all current and future beneficiaries, or about 23 percent, if the reductions were applied only to those who become initially eligible for benefits in 2020 or later; or

- Adopt some combination of revenue increases and benefit cuts.

Implementing changes sooner would allow more generations to participate in the needed revenue increases and/or reductions in scheduled benefits, thereby spreading out the necessary changes among more current age groups and lowering the magnitude required. Postponing action to address the issue would concentrate the necessary reforms on fewer generations, thereby increasing the required magnitude of the changes. If lawmakers were to take no action to address Social Security’s solvency before the combined trust funds are projected to be depleted in 2035, restoring 75-year solvency at that time would require Congress to:

- Raise revenues by an amount equivalent to an increase in the contribution rate from 6.2 to 8.3 percent on workers and their employers; or

- Cut scheduled benefits by an amount equivalent to a 25 percent reduction in benefits to all current and future beneficiaries; or

- Adopt some combination of revenue increases and benefit cuts.

In short, the sooner lawmakers undertake measures to restore long-term solvency to Social Security, the more modest the necessary reforms will be.

What will Social Security cost as a share of the total economy?

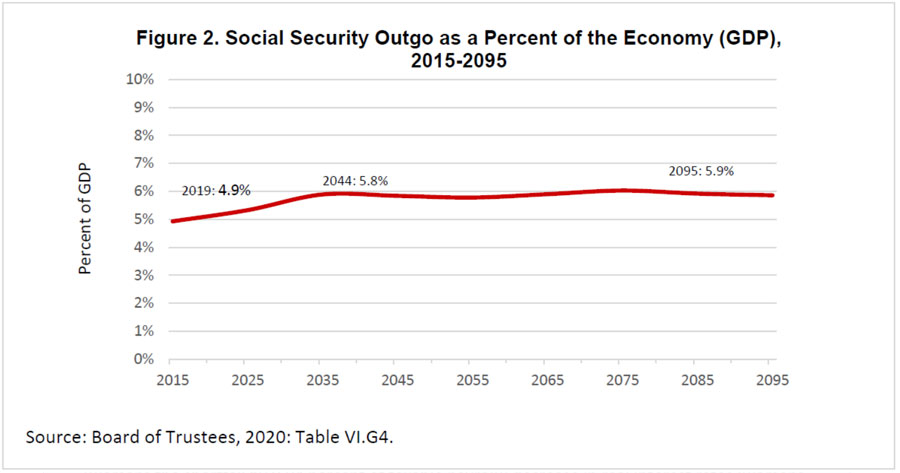

A widely accepted way to assess Social Security’s future affordability is to compare benefits scheduled to be paid under current law with the size of the entire economy – gross domestic product (GDP) – at the time. In 2019, Social Security outgo was 4.9 percent of GDP. It is projected to rise to 5.9 percent of the economy in 2038. The projected increase is driven by the growth in the beneficiary population as the Boomer generation retires.25 The increase in outgo is lower than it would be otherwise, due to a decline in benefits relative to projected earnings. This is a result primarily of the ongoing increase in the retirement age from 65 to 67, as well as additional factors such as a projected decline in the share of total worker compensation subject to the payroll tax.26 After 2039,

Social Security outgo as a percent of GDP will remain steady between about 5.8 and 6.0 percent of the economy (Figure 2).

What happens to the Social Security reserves?

The yield on Social Security’s reserves averaged 2.8 percent in 2019.27 Interest earned on individual securities ranges from 1.375 percent to 5.125 percent, depending on the year when issued.28 The annual interest earned on these securities is credited to Social Security’s trust funds. Unlike other Treasury securities, those held by the Social Security trust funds may be redeemed at par whenever needed to pay Social Security benefits.29 The Treasury bills, notes, and bonds that make up most of Social Security’s reserves are considered extremely safe investments because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. Private pension funds maintain large investments in U.S. bonds, as do many institutional investors and foreign governments.

The sum of all Treasury securities makes up the gross national debt. Most of the debt (approximately 74 percent) is held by (that is, owed to) the public: individuals, corporations, and other investors in the United States and abroad who have lent money to the government by investing in government securities.30 At the end of 2019, almost 13 percent of the national debt was owed to the Social Security trust funds, and another 14 percent was owed to all other federal trust funds or accounts.

Some people express concern when they hear that Social Security’s reserves are lent to the U.S. Treasury. This is not a misuse of Social Security funds. This procedure has the advantage of investing Social Security’s reserves in one of the safest financial instruments available.32 The Treasury securities held by the trust funds are a binding legal commitment requiring the Treasury to redeem the securities with interest when the money is needed to pay Social Security benefits. The promise of the U.S. Treasury to pay its obligations has never been broken.

What is the relationship between Social Security’s income and outgo?

Social Security’s total income exceeded outgo by $2.5 billion in 2019, but outgo is projected to slightly exceed income starting in 2021. Figure 3 shows Social Security’s income — from payroll contributions, interest on reserves, and taxation of benefits — and outgo for 2019 and as projected for 2020 and 2021.

Starting in 2021, Social Security will begin to draw down its reserves, currently at $2.9 trillion, to pay full scheduled benefits.

How can policymakers address Social Security’s projected long-term shortfall?

Policymakers have many options to prevent the Social Security trust funds from becoming depleted over the 75- year projection period and beyond.33 In doing so, Congress must also keep in mind the purpose of Social Security, which is to provide a solid foundation for retirement income adequacy. With the decline of the defined benefit pension system, decades of wage stagnation, and growing income and wealth inequality, half of today’s workers are at risk of being unable to maintain their pre-retirement standard of living in retirement.34 Hence, the policy options enacted in the next round of Social Security reform will likely include some measures that raise revenues, some that cut benefits, and some that improve benefit adequacy for certain vulnerable groups.

Conclusion

Projections indicate that scheduled Social Security benefits can be paid in full over the next 15 years with no change in current law. If nothing is done to restore long-term balance during the next 15 years, benefits will be abruptly cut in 2035. To avoid that eventuality, Congress would need to act before then to close the funding gap. The sooner lawmakers act, the more modest the revenue increases and/or benefit cuts required to bring the program into long-term balance will be. Timely action will ensure that cumulative Social Security revenues cover all statutory benefits for the next 75 years and beyond, just as they have done over the last 80 years.

dddddddddddddddddd